Use the Personal Infinitive in Portuguese like We Do

Our hypothetical student Janet has reached the intermediate level. She is so happy. Now she can keep more conversations with more ease and doesn’t need to think too much about what she wants to say.

But —

She still gets corrected a lot in a specific area of her language: the personal infinitive in Portuguese.

It was hard enough for her to overcome her habit of using the gerund… Getting around to mastering the future subjunctive… And now she was told that she has to “conjugate” the verbs that apparently have no conjugation.

How come?

What Is the Personal Infinitive in Portuguese?

First, just as a quick refresher, what’s the infinitive? You may have stumbled upon quite confusing definitions.

Let’s not do that here, okay?

The infinitive is simply the verb that you find in the dictionary.

The same form and shape.

For example, dizer. You’ll never see digo, diga, disse on the pages of a dictionary.

Now that we are past that question, let me answer the main one.

The personal infinitive is the infinitive with conjugation endings.

It is used in very specific situations, and nowadays in Brazil, it’s being used less and less.

Good news for you 🙂

But the point is, even though in many situations it is optional, the personal infinitive still gives you more precision in what you say. Also, it can be a good way to escape from the subjunctive as you’ll see in a moment.

But When Do I Have to Use the Personal Infinitive?

Good question.

There are specific situations with prepositions and verb combinations that will require your use of the personal infinitive.

In general, whenever you have a sentence without a clear subject, you should use the personal infinitive.

- Estudar português é divertido. Learning Portuguese is fun.

- Falar rápido é muito difícil. Speaking fast is very hard.

As you can see, in both examples above the verb is the subject. In English, you use the gerund. In general, if you’re using the gerund in English as a subject or object (and you can learn more about the gerund by following this link), the personal infinitive is the form you would resort to in Portuguese.

Now —

We are going to take a look at them one by one, and I’ll make notes along the way.

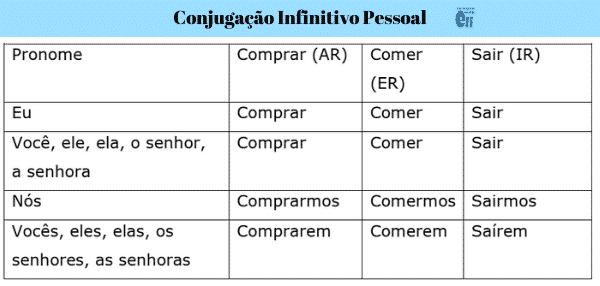

Basic forms (from our exclusive guide—more on it in a moment)

Impersonal Expressions

Impersonal expressions are those that obey the following structure:

it + be + adjective + verb+relevant endings

- É importante estudarmos português. it’s important that we study Portuguese.

- É necessário eu ir mais cedo. It’s necessary that I go earlier.

- Seria conveniente nós irmos It would be convenient for us to go now.

In the third example, the adjective comes from a verb — as many adjectives do. You could use the same structure with the original verb.

- Convém-nos ir agora. It convenes us to go now.

But it sounds to formal and it’s quite rare in spoken Portuguese.

With Specific Prepositions

Sem (without)

- Não dá para falar português sem praticar todos os dias. You can’t speak Portuguese without practicing every day.

- Sem terminarmos o trabalho hoje, não vamos conseguir ganhar esse cliente. Without finishing the job today, we’ll not be able to close the deal with this client.

The most common mistake with this preposition is using the gerund in Portuguese. It really doesn’t sound natural as I discussed in this article about the most common mistakes you might make in Portuguese.

Para (In Order [for] to)

You’ve probably learned the structure “para que” to express “in order [for] to”. That structure uses the subjunctive — either past or present. This structure you’re about to learn uses the personal infinitive. Both structures can be used to express the same meaning.

- Eu comprei este filme para nós assistirmos. I bought this movie for us to watch.

- Este remédio é para você tomar. This medicine is for you to take.

Por (Because)

- Por entendermos a importância de ter uma boa saúde, estamos oferecendo um mês de academia grátis. Because we understand the importance of having good health, we are offering a free month of gym membership.

- Por saberem que o dia ia ser difícil, eles decidiram chegar um pouco mais cedo. Because they knew the day was going to be harsh, the decided to get there a little bit earlier.

You’ll see here that it’s a single preposition (for). You don’t use “porque” at the beginning of a sentence. Many Brazilians do, but it sounds a bit archaic, literary, and not so natural.

Ao (upon, when)

- Ao chegar em casa, Anitta decidiu escutar música. Upon arriving at home, Anita decided to listen to music.

- Ao falar com o professor, percebi que não conhecia o vocabulário necessário. When I spoke with the teacher, I realized I didn’t know the necessary vocabulary.

As you have noticed from the translation of the second example, “ao” can also express “when” as in when you get home please call me.

You cannot use it to express “when are you going home?”

Até (Until)

- Até eu entender o que diz essa frase não vou continuar a ler. Until I understand what this sentence says I’m not keeping on reading.

- Você vai ficar aqui até eles chegarem. You’re going to stay here until they arrive.

Again, you might have learned an alternative structure (até que) that requires the subjunctive. Although in some situations they have the same meaning, there is a difference — more on that in a minute.

No caso de (In case)

- No caso de eles chegarem, por favor, diga a eles que me esperem. In case they arrive, please, tell them to wait for me.

- Você pode ficar com o meu livro no caso de eu precisar sair? Can you keep my book in case I need to go away? Thank you.

You could simply use “caso” with the subjunctive here. But remember that whenever you use the subjunctive, you have to decide which tents you want to use.

And if you’re not so familiar with the Portuguese tenses, it’s your lucky day. I’ve prepared a special report for you to use the tenses with ease and say goodbye to the confusion and frustration of translating everything in your head and still getting everything wrong.

Depois (After)

- Você só vai poder brincar depois de comer tudo. You’ll only play after you eat everything.

- Depois de estudar tanto, estou morto de cansado. After studying so much, I’m dead tired.

Good grief, isn’t it getting repetitive?

You could use the subjunctive to with an alternative structure (depois que)! The basic sense is the same, but depending on context you could mean something slightly — and importantly — different.

Antes de (Before)

- Antes de sair, apague a luz. Before you leave, turn off the lights.

- Você deve pensar antes de falar. You must think before speaking.

Alternative structure: antes que + subjunctive (yep!)

Apesar de (although)

- Apesar de entendermos as suas razões, não podemos aceitar as suas desculpas. Although we understand your reasons, we cannot accept your apologies.

- Ele não fez um bom trabalho, apesar de ser muito inteligente. He didn’t do a good job, although he is very smart.

A synonym for that expression is “go away”. But it requires the subjunctive instead of the infinitive.

With Verbs That Deal with Perception and Cause

Some verbs dealing with perception (ver, sentir, ouvir) and cause (fazer, deixar, mandar) may also require the use of this form.

In general, Brazilians tend to prefer the inflected forms. That means, the form of the verb without the endings.

But using the inflections might help you express what you want more clearly.

I will indicate the preferred forms between parentheses.

- Deixe minha irmã entrar, por favor. Please let my sister in.

- Mandei a Paula e o Tiago comprarem/comprar um bolo para nosso aniversário. (optional) I had Paula and Jack go buy a cake for our birthday.

- Eu os vi correr. Eu os vi correrem. (optional, too) I saw them run.

When the Subject Is the Same in Both Clauses

It tends to be optional.

- Estamos aqui para dizer o que pensamos. (preferred)

- Estamos aqui para dizermos o que pensamos.

We are here to say what we think.

Infinitive or Subjunctive?

I said before that you can use the personal infinitive to escape from the subjunctive. Although that may be true in most situations, and some of them there is a slightly different meaning that you might want to take into account.

And just a disclaimer.

You will never be able to grasp everything at once without practice. So, whenever you have Portuguese classes you want to pay attention to how your teacher speaks. Also, when reading Portuguese books, you want to take notes on the usage that you see on the page.

In the example below, both sentences can be translated as:

Before you leave, turn off the lights.

- Antes de sair, apague a luz.

- Antes que você saia, apague a luz.

But in our perception, using the subjunctive can render the sentence more formal and immediate.

The sentence (1) is way more common.

There might be other differences, but they will depend on each case.

Now that you know way more about the personal infinitive in Portuguese, why not pick up the whole thing?

Grab your free report on the Portuguese tenses right now.

You’ll speak with more confidence if you know what to say when. And this book is going to help you learn that part.

The best is that it’s free!

And if you’re ready to tackle more Portuguese grammar questions, head over to our grammar section and look around.

The PwE Continuing Education Program

At last, a resource to help you understand more of what you hear in Portuguese. This program is the only one to provide you with an in-depth lesson each week without you having to show up! Learn more.

Overall good content! But, you should check this sentence translation “Convém-nos ir agora.” to English. It should be something like “We should go now.”