Use the Days of The Week in Portuguese like a Boss

Although nothing seems to be quite straightforward in our language, using the days of the week in Portuguese is actually straightforward – once you understand the logic behind it.

Days of the Week in Portuguese and Religion

As you probably know, Portuguese as we know it has been influenced by religion since times immemorial.

You probably heard someone saying thank God in Brazil even though that person might be an overt atheist.

And with the days of the week, it is no different.

Let’s start with the word for Sunday.

As you probably know, it’s “domingo.”

If you speak Spanish, you’ll see it’s the same word.

It comes from the expression “Dies Dominica,” or “the day of the Lord.” That’s the day when God finished creating the world and wanted to take a rest.

That’s why in many Portuguese speaking countries – and many other countries for that matter – nobody should work (or works) on Sundays.

So, that Latin expression became our modern-day “domingo.”

The Weekdays

On that day, farmers would go to the street fairs to sell their produce. It was a very busy day for everybody, and every following day farmers would do the same.

Every day between domingo and sábado (Saturday) would be called then a “fair day.” Because people work on those days, they’re also called dias úteis, or “useful days.”

The first fair took place on Sunday. The Portuguese for that would be “primeira feira” (“first fair”). But that was the day of the Lord, so it was christened “Domingo.”

The following days, though, would each receive the corresponding day of its fair. Thus, we ended up with the following days of the week in Portuguese:

- Segunda-feira (second fair, or Monday)

- Terça-feira. (Third fair, or Tuesday)

- Quarta-feira (Wednesday)

- Quinta-feira (Thursday)

- Sexta-feira (Friday)

- Saturday also received influence from religious vocabulary. The word “Shabbat” became then “sábado” (Saturday).

- And finally, Domingo for Sunday.

In Spanish, French, and Italian, they’ve kept the astrological origins for the days of the week – lunes, martes, miércoles… (Moon, Mars, Mercury…). But we’re Portuguese – we’re different.

Grammatical considerations

👉 Days of the week in Portuguese are gendered nouns.

That means you have to add either “o” or “a” (or another article) in front of them.

Weekdays are feminine (-feira), whereas the days of the weekend are masculine.

👉 When writing, you should use the full form of the word.

- Eu vou trabalhar na segunda-feira. I am going to work on Monday.

But, when speaking we hardly ever use the ending -feira.

- A: O que você vai fazer no sábado? A: what are you going to do on Saturday?

- B: No próximo sábado, vamos viajar para a Alemanha. B: next Saturday, we are going to travel to Germany.

We also avoid using the ending -feira to ensure we’ll not repeat a word.

- Nessa semana, trabalho na segunda, na terça e na quarta. This week, I work on Monday, on Tuesday, and on Wednesday.

- O que você vai fazer terça e quinta? What are we going to do on Tuesday and Thursday?

One of the things that pester my English-speaking friends is plurals. I’m sad to say that you have to pay attention to plurals also in using days of the week in Portuguese.

Every element of those words goes to plural.

- Às segundas-feiras, tenho folga. Mas às terças-feiras eu trabalho. On Mondays, I don’t work. But on Tuesdays I do.

A secret Brazilians usually ignore

I say that not to make you feel good but… You’re about to learn something that we Brazilians usually ignore.

When we talk about repeated action on a specific day of the week, we have to use the preposition “a” before it. And the word goes to plural.

- Aos sábados, estudo português. On Saturdays, I study Portuguese.

- Tenho aula de dança às quintas à tarde. I have a dance class on Thursdays in the afternoon.

However, if you’re talking about something that takes place sporadically or only once, then you have to use the preposition “em” – and remember to properly join this word with the following article.

- Na quinta, tenho aula de dança. On Thursday, I have dance class. (Only on this Thursday, probably next Thursday I don’t have anything to do.)

- Na segunda-feira, tenho que visitar minha tia. On Monday, I have to visit my aunt. (Only this Monday, next Monday I’m totally free.)

When I say Brazilians ignore this fact, I mean that we usually mix both, and we are not very clear.

But if you intend to take CELPE-BRAS – or want to have a good and respectable Portuguese – paying attention to this rule will set you apart.

Two Bonuses

First, in street signs and other forms of quick communication, we don’t really write “segunda-feira.” You can use “2º-feira” instead.

Thus, if something’s open from Monday to Friday, you see:

- Aberto de 2º à 6º.

We always write sábado and domingo in full.

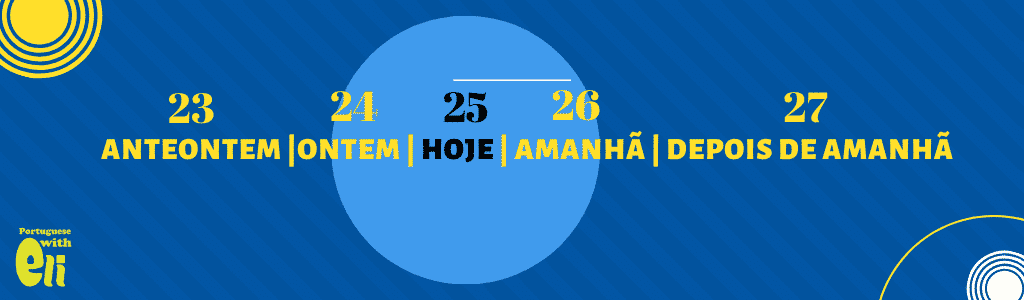

And something I find very hard to do in foreign languages is talk about the time when involving different days.

Yesterday, today, tomorrow, the day after tomorrow – not all languages have the same concepts.

That’s why I prepared this little chart… To give you a visual representation of the way we speak here in Brazil about a sequence of days.

Well, that’s it for this article. And it’s reasonable to assume that you need to talk about the time when telling whether something is taking place on Segunda ou Sexta. If that’s the case, you can go here and find out a bit more about it.

Head over to the grammar section if you want to learn how you can put those words to use.