Talking about Family in Portuguese is… EASY

If you’ve met an average Brazilian, you probably know that they have many family members who live with them. Some may be part of their immediate family; some may be more distant. The fact is, talking about family in Portuguese may be confusing.

That’s because Brazilians tend to stick together. And if someone comes in along the way, they are also absorbed by the family institution. Quickly, the “extended family” in Brazil becomes quite extensive indeed.

So, for this Portuguese vocabulary lesson, we will discuss how to say mom, dad, son, children… All those words in Portuguese.

But let’s make it interesting. Let’s transform it into a story.

I’ll be making comments along the way.

Basics on the Family in Portuguese

It can get quite complicated.

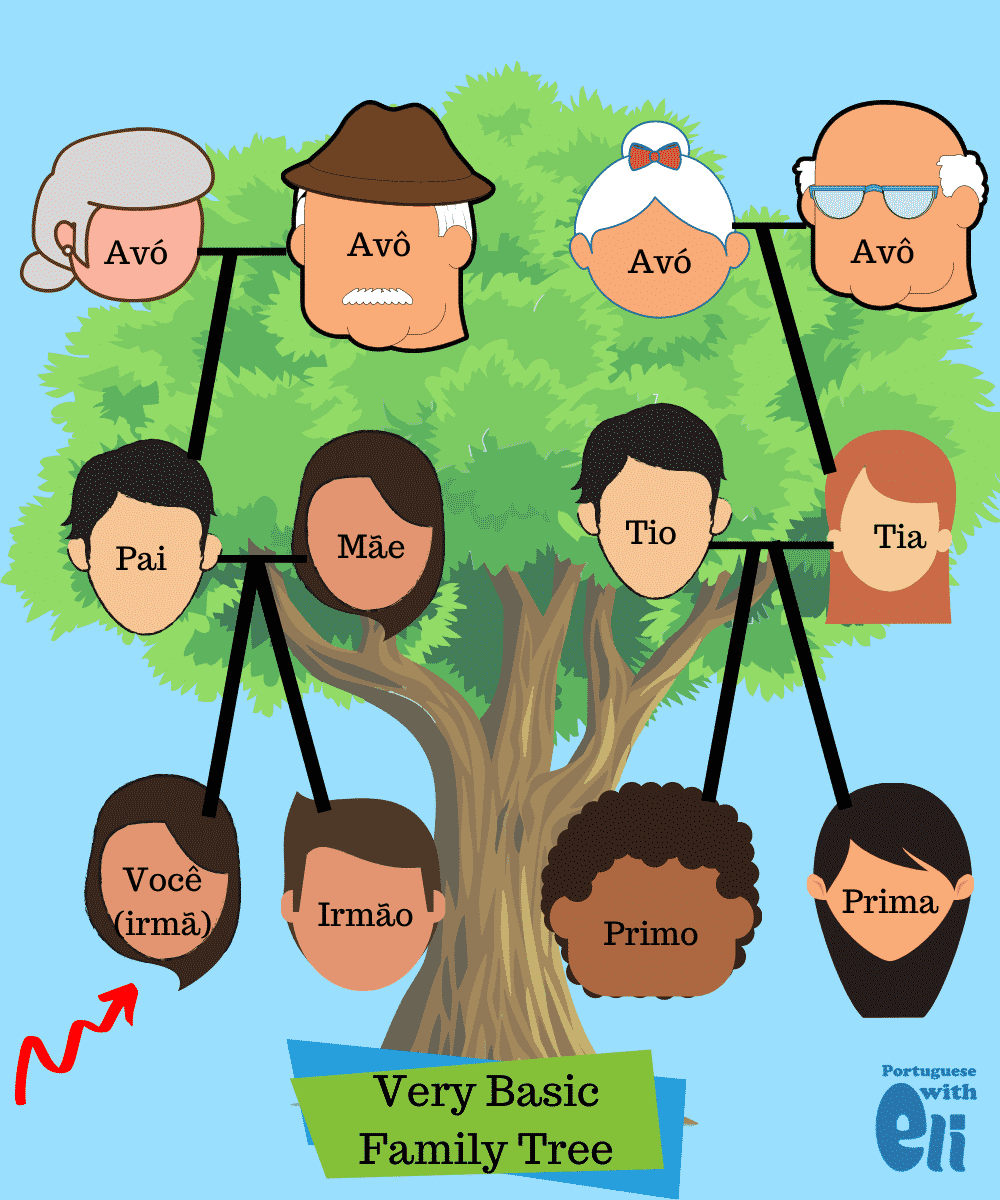

If you look at the family tree — you are the little sister on the lower-left corner of the picture — you see that it’s pretty straightforward.

But how do you express some more complex family ties such as niece, nephew, brother and sister-in-law, siblings… In Portuguese?

First, let’s get this problem out of the way.

Two false friends are “relative” and “parent”.

In Portuguese, the look-alike word of relative means “related to” or “relative” as when you use the adverb “relatively easy”. It doesn’t mean “relative” at all.

Now, the false cognate “parent” in Portuguese means “relative”.

And how do you say “parent”?

If you want to say “parents” then use the plural form of “father” (pais). If you want to say, “I’m a single parent”, you must say something like, “I’m a single mom/dad.”

Parente em Primeiro, Segundo, Terceiro e Quarto Grau

You can skip this part. This is just for those who are into legal matters related to family ties.

In Portuguese, we have a concept of “first-degree relativeness”. We use it only in legal contexts. It helps us see how we are related to someone else — my father is my relative of first-degree, and my grandfather is my relative of second degree. My uncle is a third-degree relative, because the bloodline has to go back to my grandfather (two degrees) then forward it to my uncle — one more degree.

But as I said, you won’t hear this as much. Only when Brazilians talk about cousins — but usually they are wrong about that.

A Quick Recap So Far

- Parentes e pais não são a mesma coisa em português. É bom ter atenção. Relatives and parents are not the same thing in Portuguese. You had better pay attention to it.

- O filho de um primo não é considerado nosso parente. A cousin’s son isn’t considered our relative.

- O João é meu parente de sangue. Já a Carla é minha parente por afinidade. John and I have blood ties. Carla, on the other hand, is my relative by affinity.

- A relação de um pai de um filho adotivo é de parentesco civil. Eles podem não ser parentes consanguíneos ou naturais na lei brasileira, mas eles são parentes mesmo assim. The relationship between a father and adoptive son is that of civil relatives. They may not be related by blood under Brazilian law, but they are relatives all the same.

Your Immediate Family in Portuguese

In Portuguese, we usually say “nuclear family” we want to talk about our immediate family.

I think immediate family is a more accurate term, but I have known families who would welcome the term “nuclear”.

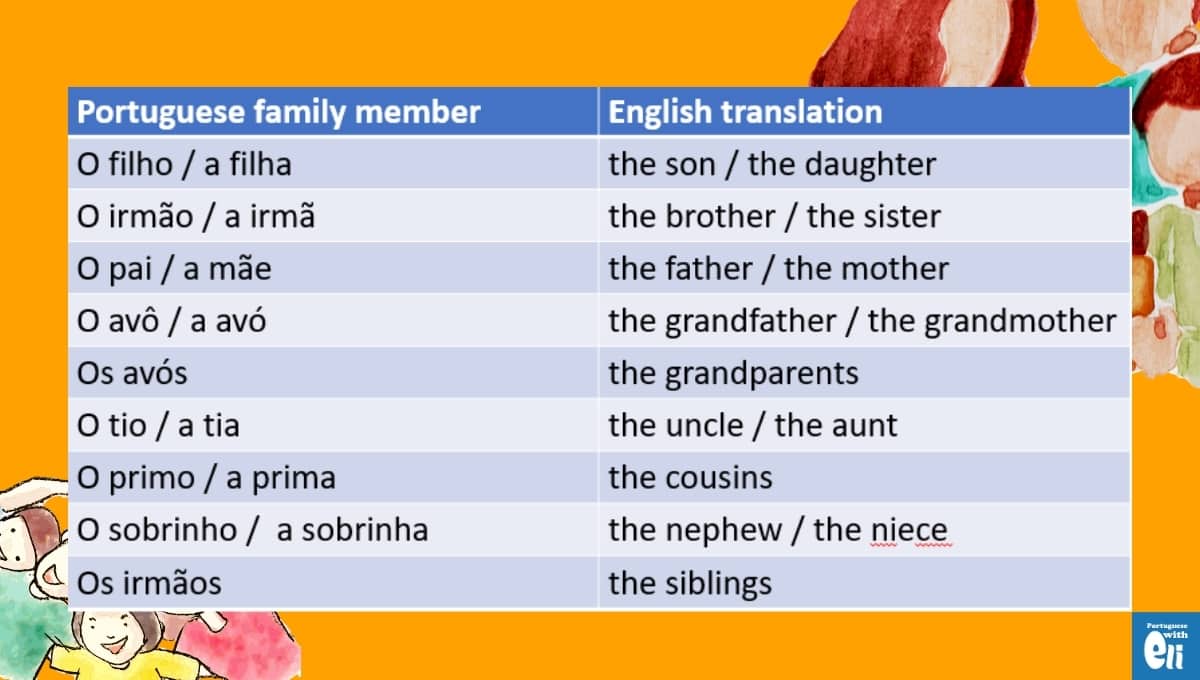

The basic words are as follows:

And here are some examples for you to check and practice with. Pay attention to how we express certain concepts in Portuguese, as in the first example.

- Na minha família somos cinco filhos. In my family there are five children.

We use “somos X” to say, “there are x of us”, as in the soap opera “Éramos Seis”, or there were six of us. Weird.

- A Paula é a filha mais velha. Paula is the eldest daughter.

- O Ricardo é o filho do meio. Ricardo is the middle son.

- E eu sou o caçula, o filho mais novo. And I am the Benjamin, the youngest son.

- Meu pai se chama Abelardo minha mãe se chama Ticiane. My father is called Abelardo and my mother is called Ticiane.

- Os meus avós paternos moram com a gente. My paternal grandparents live with us.

And yep, we usually talk about which side the grandparents belong to.

- O meu avô é o Antônio e a minha avó é a Camila. My grandfather is Antonio and my grandmother is Camila.

- Já os meus avós maternos moram em São Paulo. My maternal grandparents, on the other hand, live in São Paulo.

- Minha mãe é filha única. Mas meu pai tem oito irmãos. My mother is an only child. But my father has eight siblings.

- Isso significa que eu tenho no total oito tios e tias. That means I have in total eight uncles and aunts.

- Também tenho muitos primos e primas, já perdi até a conta. I also have many cousins. I even lost count.

- E eu também tenho um sobrinho e duas sobrinhas, todos filhos do mesmo pai. I also have a nephew and two nieces; they are all children of the same father.

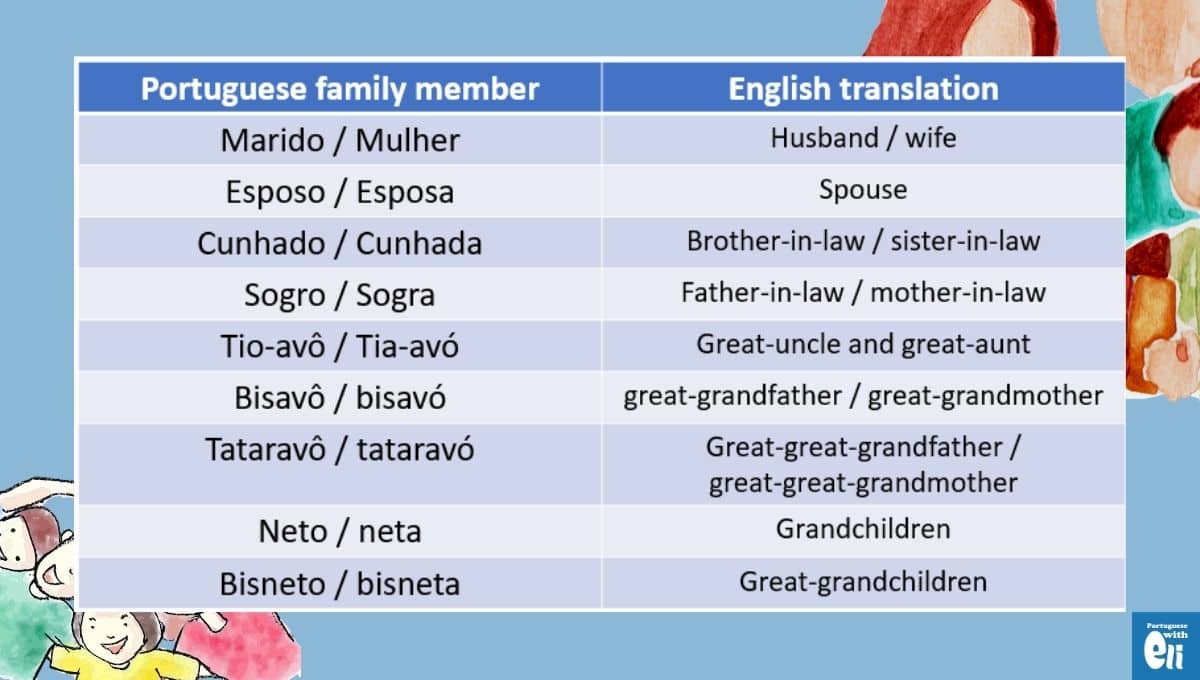

Once Someone Marries… Extended Family—In-Laws in Portuguese

Marriage has been known to expand families to unbearable numbers.

And when talking about family and extended family in Portuguese, you’ll see that our language has learned to cope with this phenomenon well.

And more examples for you:

- Na igreja, o padre diz: eu os declaro marido e mulher. In the church, the father says: I declare you husband and wife.

- Mas no cartório, na linha pontilhada, eles são esposo e esposa. But in the registry, on the dotted line, they are spouses.

- Os irmãos da minha esposa são os meus cunhados e cunhadas. My wife’s siblings are my brothers-in-law and my sisters-in-law.

- E aqui no Brasil, brincamos que cunhado não é parente. And here in Brazil, we joke that a brother in law is not a relative.

- O pai da minha esposa é meu sogro. Mas quando estamos no churrasco, ele é meu sogrão. My wife’s father is my father in law. But when we are in the barbecue, he is my big father in law.

- A mãe da minha esposa é minha sogra. Nós somos bons amigos, sempre que estamos longe. Quando estamos perto um do outro, somos inimigos. My wife’s mother is my mother-in-law. We’re good friends whenever we are far from each other. When we are close, we are enemies.

- Para complicar um pouco, o marido da minha cunhada é meu concunhado. Mas dificilmente usamos essa palavra. Just to make things a little bit more complicated, my sister-in-law’s husband is my “concunhado”. But we hardly ever use that word.

People You Rarely See

And some more examples about those people you rarely see.

- Às vezes no Natal, às vezes no funeral: sempre encontramos nossas tias-avós e nossos tios-avôs. Sometimes at Christmas, sometimes in the funeral: we always meet our great-aunts and great-uncles.

- Eu não tenho mais bisavô nem bisavó. Os dois faleceram há muito tempo. I don’t have great grandfather and great-grandmother. Both passed away a long time ago.

- De tataravô ou tataravó então… nem se fala. As for great-great-grandfather and great-great-grandmother… They are long gone.

- Quando eu completar 65 anos, espero ter muitos netos e netas e bisnetos e bisnetas. When I turn fifty-five, I hope I have many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Half-Siblings

When writing it, mind the hyphen. And remember: “meio” (half) agrees with the noun it precedes.

- E minha irmã mais velha é minha meia-irmã. Somos filhos do mesmo pai, mas de mães diferentes. My oldest sister is my half-sister. We are children from the same father but different mothers.

Idioms about the Brazilian Family

And yes, we do have lots of idioms involving family. Usually they are not good idioms. The ones you’ll see here are highly frequent. You can start using them right away.

- Em briga de marido é mulher, ninguém mete a colher. You don’t interfere in a husband-wife fight.

- Fulana é mulher de família. Jane Doe is a respectable woman.

- Eu puxo a meu pai. I take after my father.

- Fulano é escarrado e cuspido o pai. John Doe is an identical copy of his father.

Terms of Endearment

The terms of endearment to talk with family in Portuguese usually revolve around using diminutive words — those little suffixes that we append to words and make them look bigger but feel smaller and cozier.

- Meu filhote, minha filhota — My dear son, my dear daughter. It also sounds like my baby.

- Filhinho e Filhinha. — Little Son, Little daughter

- Vovô / Vovó — Granddad, Grandma

- Vovozinho / Vovozinha — Granddaddy, Granny

- Mamãezinha / Papaizinho — Mommy / Daddy

- Papai / Mamãe — Dad / Mom

- Mainha / Painho — a variant spoken in Bahia and other neighboring states.

And in Brazil, families are so important and traditional that a TV show called “A Grande Família (Wikipedia)” was on air for 485 episodes and 10+ years combined.

It’s a great exercise if you want to watch some episodes of it on YouTube.

And if you want to learn more vocabulary, why not grab your report to use the tenses correctly and subscribe to my daily newsletter with new stories that are engrossing and enticing and help you learn Portuguese even faster? Do it now 🙂

And for more vocabulary lessons, check out our vocabulary section.